dodis.ch/52927

Memo1 bythe Austrian Ministry of Foreign Affairs

The Specter of German Reunification

A specter is haunting Europe. The specter of German reunification, and itscares the Western Europeans. This fear – rarely acknowledged – is behind manydiscussions about the future of European security.

The two superpowers are apparently less bound by fear. One sometimes hears from boththe US and the USSR that German “reunification” is not only possible, but perhapseven desirable. The expectations of the US and the USSR are, however, contradictory:The United States expects that a reunified Germany would push against the East, andweaken the USSR. The Soviet Union expects that a reunified Germany would step out ofNATO, and thus fatally weaken NATO.

This discussion of German reunification is surprising in some respects. After all,because of its treaties with the East, through its recognition of the GDR, andthrough its involvement in the CSCE process, the FRG seemed to have finally andirrevocably accepted the status quo in Europe and thus the existence of two

German states, and without ulterior motives. Against the backdrop of these hardfacts, the question begs to be asked: How serious is this new flare-up talk ofreunification? Is there really nothing more to it than a mere superficial and purelyverbal response to the advance of the right-wing nationalist “Republicans” in theFRG? Or is it to be taken more seriously?

The question was broached at the Ambassadors’ Conference in early September. Theambassadors in both Berlin2 and Bonn3 were unanimously convinced that this talk isnot to be taken seriously. Nobody in a position of political responsibility,according to the Austrian ambassador in Bonn, would really aim for a “reunification”with the GDR.4 The coexistence of the two states would beaccepted by virtually all. The maximum goal supported by almost all political partieswould merely be a “Germany policy” that intensifies existing contacts between bothStates at all levels.

The Austrian Ambassador in Berlin claimed there was no great pressure for radicalchanges in the GDR. Sudden outbursts and changes of course are not to be expected.Because it works on the whole, the state would also be accepted by thepopulation.

The opinions expressed by the two ambassadors describe – probably accurately – thecurrent state, which is not a given. They assume that this state will essentiallyremain unchanged. This may be correct, but need not be so. There is some evidencethat attitudes toward “reunification” are changing in the two German states. In thetwo German states, there are signs of a fundamental change in the political climate.In the FRG, for example, the Historians’ Dispute (in which German war-guilt wasrelativized) changed the emotional-political framework in which postwar internationalrelations were anchored. Three to four years ago it would have been unthinkable thatthe Polish-German border would be called into question again by a high-rankingpolitician and many years after its recognition by the Warsaw Treaty.

Three or four years ago this would have signified the end of every political career.Not so today. A whole new attitude towards the European East has established itself–obviously and gradually there is a renewed belief in a special “German mission in theEast.” This mission goes far beyond the “Ostpolitik” of Willy Brandt5. Its essential goal had only been the acceptance of thestatus quo. But the objectives of today’s German Ostpolitik are more ambitious. Intheir new nationalism, the aggressive advocacy of unification, and their skepticismtowards the west and European integration the right-wing “Republicans” are thus asymptom of a political change in mood that encompasses more than just theirvoters.

The GDR appears to be the most solid of the communist states – especially in economicterms. Nevertheless, this country has political feet of clay. The binding power ofcommunist ideology has – if it ever was great – anyhow disappeared. This alsohappened in other communist countries. These other states, however, base their socialcohesion and identity on something other than communist ideology – on religion or –mostly – on nationalism. There is probably no such thing as GDR nationalism. At best,there is a certain feeling of connection with their homeland. One probably got usedto some convenient facilities of “real existing socialism” in the GDR – such assecure jobs, cheap food staples and apartments, etc. But that alone does not secureidentity, and this comfort will gradually wane in the course of necessary economicreforms, which will come sooner or later, even in the GDR. Likewise, it is becomingincreasingly difficult to hold the state together with dictatorial measures. Where,if not mainly to the FRG, would the GDR turn if its economic and political openingcan no longer be delayed?

Reunification may, therefore, very well be on the future political agenda of the twoGerman states. Formally, the other – and especially Western European – states cannotobject. The principle of self-determination is recognized internationally. Thisprinciple will not be questioned openly by any Western European country and not whenapplied to the two German states. Actually, no one wants a real application of thisprinciple by a “reunification.” This fear, however, is not articulated openly. One isonly too aware of the fact that taking an open stand against reunification would onlystrengthen the extreme and nationalist forces in the Federal Republic. Hence, thereis no open political dialogue with the FRG on this issue – only unadmitted silentfear.

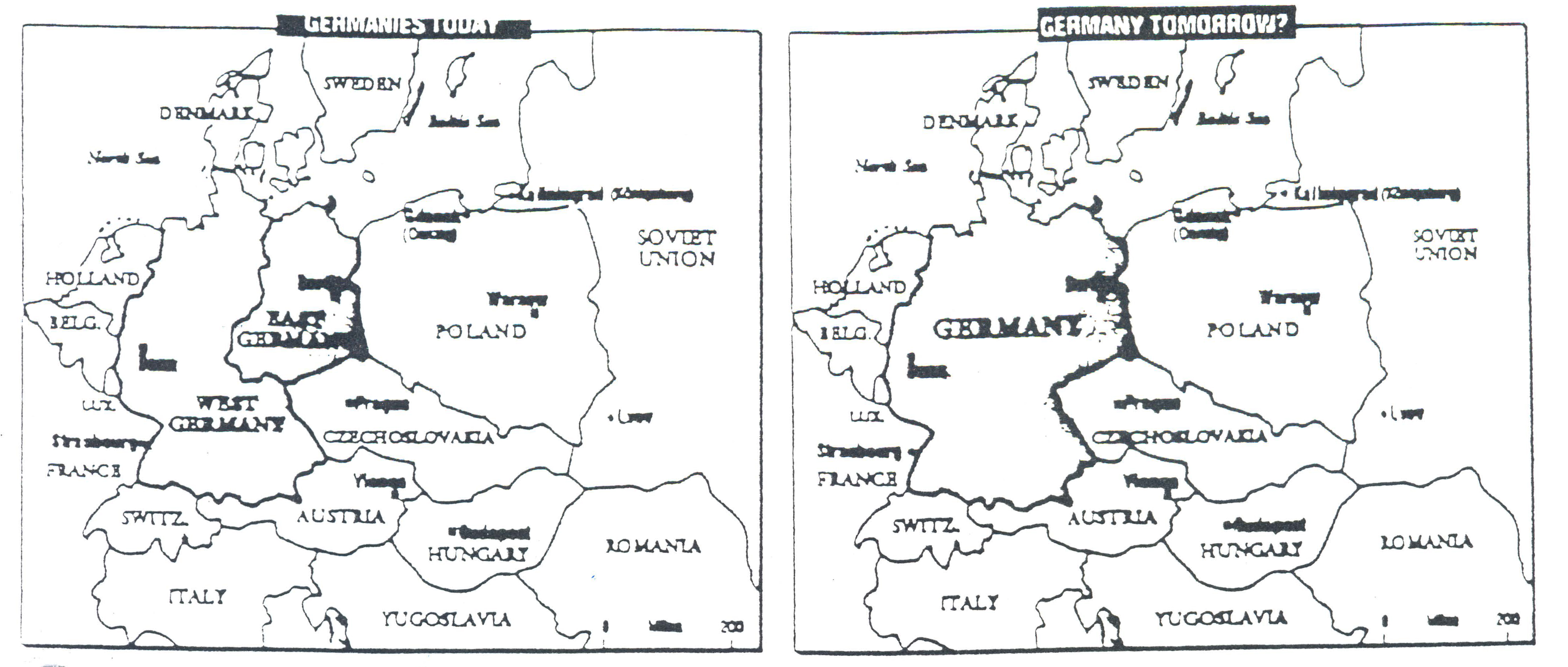

If, in what form, and when there is a merger of the German states, is certainlyuncertain. In any case, the desire for “reunification” in both German states cannotbe ruled out, especially in the FRG, once it ceases to be a merely abstract anddistant goal and becomes a specific concern. One should thus take the possibility ofa reunification seriously and really examine what the consequences would be. Wouldsuch a reunification actually blow up the entire postwar order?

Reunification would certainly be a huge shock for this order. It is argued below thatthe European postwar order would not have to fall apart because of this. Even areunified Germany would not be so strong that it would dominate the Europeancontinent economically and militarily. It would just be a very big country among theother major European states.

| Inhabitants 1985 | Inhabitants 2025 | Surface in km2 | |

| FRG | 61.0 | 57.2 | 249,000 |

| GDR | 16.6 | 17.3 | 108,000 |

| Together | 77.6 | 74.5 | 357,000 |

| France | 55.2 | 63.7 | 547.000 |

| Italy | 57.1 | 58.5 | 301.000 |

| Czechoslovakia | 17.5 | 18.5 | 127.000 |

| Poland | 37.2 | 48.0 | 312.000 |

| Together | 54.7 | 66.5 | 439.000 |

The surface of a reunified Germany would be 357,000 km2, far less thanthe combined area of Poland and Czechoslovakia (439,000 km2).

In the GDR, the population is growing slowly, in West Germany it is dropping sharply.In 2025, a “unified Germany” would have a population of 74.5 million. France would,in contrast, have a population of 63.7 million, and Czechoslovakia and Polandtogether would have a combined population of 66.5 million.

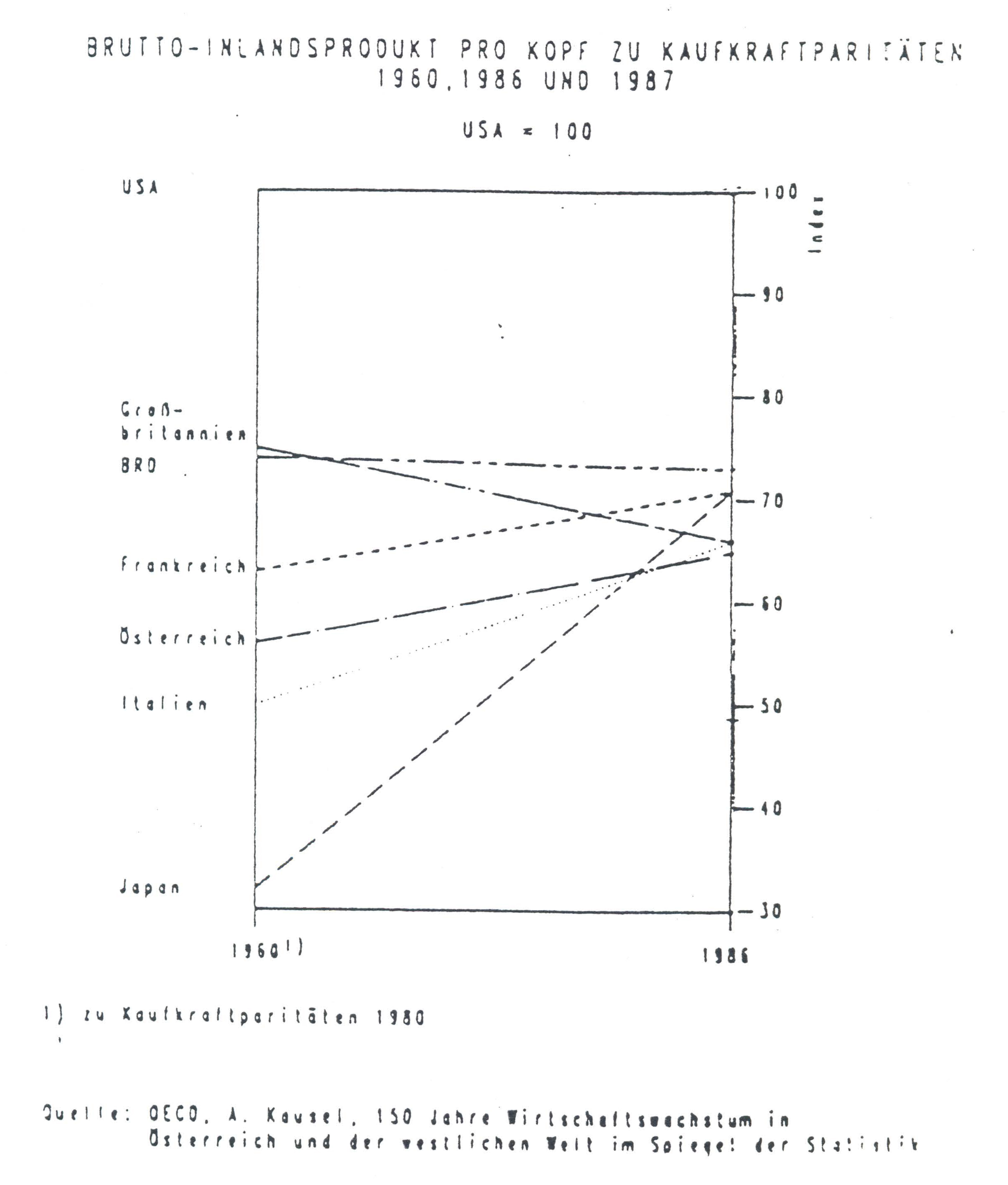

Not only is the FRG’s population growth low (or even negative), the FRG’s economy isalso far less dynamic than itself and other European countries assume. The mostreliable measure of the development of economic power is the development ofproductivity. The development of productivity in the Federal Republic of Germany hasbeen slow since 1960 and risen far less than in either France or Italy.

These trends are likely to continue, and in 10 years at the latest France will havecaught up in absolute economic power with the FRG.

One must assume that even with reunification the current GDR could not immediately bebrought up to the economic level of the FRG. One could therefore assume that theproductivity of the area that is the GDR today, even in 2025, would be somewhere –perhaps around 15% – below the productivity of the current FRG. The entire economicpotential of the two unified areas would therefore in 2025 approximately match theeconomic power that France will then have.

The economic power of a “unified Germany” must not just be compared with France, butalso with the rest of the Western European states. Above all, the southern ECcountries (such as Italy and Spain) will – as in the past, but also in the future –develop more rapidly economically, so the economic and political weight of these ECcountries will increase when compared to the FRG or a “reunified Germany”.

A reunified Germany would not be significantly greater in population and economicstrength than the FRG is today: namely, one among the most powerful nations ofEurope.

The consequences of a “reunification” cannot, however, only be looked at from apurely economic standpoint: they also need to be viewed from a military securityperspective. What would be the consequences of “reunification” in this area?

Military and Security Policy Aspects of a “Reunification”

“Reunification” is sometimes associated with a “neutralization” of the then unitedGermany. Neutralization would thus be condition or result of an association of thetwo German states.

First, as Khrushchev6 said during his tenureto the then Foreign Minister Kreisky:7 “Neutrality is astatus which is appropriate for a small country located geographically andsecurity-politics-wise between two powers.” Neutrality does not apply to a statethat, because of its own great influence, whether it wants that or not, becomes asignificant factor in international relations. The Ostpolitik of a reunified Germany,even if that state is formally “neutral”, in practice would not be neutral. Whatevera large state undertakes has far-reaching consequences, both in the West and in theEast of the continent. For example, whether a small neutral country participates insanctions does not significantly increase or reduce the effectiveness of suchsanctions, but whether a country with more than 70 million inhabitants participates,this determines very well whether such sanctions are effective or not.

Second, a “neutralization” of the current FRG (as proposed by theneoconservative American intellectual Irving Kristol8 in the enclosed article) would weaken the Western defensealliance so much as to make it insubstantial. “Geopolitically”, geography simplyprivileges a large landmass to the east of the continent. In contrast, NATO-alliedWestern Europe has less strategic depth. If this depth were further reduced by the“neutralization” of the FRG, a military counterweight to the Soviet Union could in noway be maintained on such shrunken territory. A “balance” (or better: aconflict-hindering balance of power) would no longer exist.

Third, the neutralization of West Germany would naturally bring aboutthe withdrawal of US troops from Europe (which are stationed for the most part in theFRG). Europeans doubt – probably rightly – the ultimate effectiveness of the “nuclearguarantee” granted to them by the US. More important is the guarantee – or “hostage”function of American troops. These troops enable – more effectively than nuclearmissiles – the “coupling” of the European theater of war to the United States. Thiscoupling would be lost with the withdrawal of US troops.

Fourth, there is perhaps a problem with a reunited Germany arming itselfwith nuclear weapons. Nuclear weapons are today quite “cheap” to produce. Thetechnical know-how is certainly available in the FRG. The incentive to guaranteeone’s security in such a “cheap” way through nuclear deterrence is thereforeconsiderable. Speaking against the purchase of national nuclear weapons is certainlythe uncertainty that the possession of such weapons would trigger in Europeancountries in East and West. Speaking for the possession of nuclear weapons is thefact that a reunified and neutral Germany would be surrounded by potential enemies,who could be held at bay best and most “cheaply” with the aid of nucleardeterrence.

Fifth, one must question if the FRG stepping out of the western defensealliance would even be physically possible as things stand. The FRG is nowadays verytightly integrated economically and socially with the rest of Western Europe. ThisWestern European integration and cooperation will increasingly extend to securitymatters. The situation where European security is provided largely by the UnitedStates can historically not be maintained indefinitely. Western Europe willincreasingly have to provide for its own security – sooner rather than later.

Security policy is all-embracing. It also has a specifically economic aspect and aneconomic basis. If a “neutralized” reunified Germany were to pursue an independentsecurity policy, then the FRG would have to, at least in some important areas (suchas in technology), free itself from already existing dependencies and connectionswith Western European countries. But the integration of Western Europe has alreadyprogressed too far. This option of stepping out of Western European cooperation is nolonger open to the FRG. For example, the FRG no longer has the option to develop itsown aviation and aerospace industry separately from the rest of Western Europe.

It is of course the – acknowledged or unacknowledged – objective of the remainingWestern European countries to strengthen the integration of the FRG into WesternEurope and make it irreversible. Behind the integration-friendly policy of France isnot just France’s desire to secure its influence through a united Western Europe,which it could not exercise acting alone in today’s world. With this policy, Franceis also pursuing its objective of strengthening the “Western tying” of the FRG to anextent that makes it inextricable.

Hence, it is both unlikely and undesirable that the FRG should withdraw from NATO tobecome neutral simply in order to “unite” with the GDR. This would also not be in thelong-term interests of the Warsaw Pact and the USSR. A united Western Europe (alsoincluding the FRG) would certainly have a far less ambitious “Ostpolitik” than areunified, neutral Germany.

What would be the consequences of the more likely solution in which the reunifiedGermany does not become “neutral” and the FRG remains in the Western defensealliance? This would certainly result in a military shift at the expense of the East.But this shift is less far-reaching than one would at first assume.

The advantage that the Warsaw Pact currently draws from the fact that the GDR is amember shows itself in the light of the present – still – ruling Soviet militarydoctrine. This demands that in the event of an East-West war, Warsaw Pact troops willadvance to the Atlantic Ocean as quickly as possible in order to prevent the arrivalof reinforcements from the US. The “Spur” in the south of the GDR that protrudes intoWest Germany (“Fulda Gap”) would serve as a springboard for such an offensive.

However, it is intended and also probable that the military doctrines will bechanged. The predominant doctrines in both the West (“deep strike,” FOFA) and theEast (“forward defense”) assume “attack is the best defense”. These offensivemilitary tactics are contrary to the principally defensive strategic objectives ofthe two alliances, who just want to maintain the status quo and seek no territorialgains.

If the military alliances and, especially, the Warsaw Pact convert their “defense” toa purely defensive one, with no element of attack against Western Europe, thisremoves the goal of reaching the Atlantic coast as quickly as possible, thus loweringthe military value of the East German spur protruding into the FRG. This reduces themilitary disadvantage of withdrawing the GDR from the Warsaw Pact. The loss ofmilitarily useable terrain is hardly decisive strategically. The GDR is, in itseast-west dimensions of 200–300 km, a relatively narrow state. In contrast, the newEast-West border, also being the eastern border of a reunified Germany, would havethe advantage of being straighter than the previous military East-West border andtherefore easier to defend.

Indeed, Czechoslovakia would be more negatively affected by such a shift in themilitary dividing line to the east. Its north-west border is currently coveredagainst NATO by the GDR. If the GDR withdraws from the Warsaw Pact, this border wouldbe directly exposed to NATO. A solution to this problem could be to “demilitarize”the territory of the present GDR even after reunification with the FRG, although thereunified Germany would belong to NATO, and this demilitarization could be securedthrough international guarantees.

Summary:

Despite lip service supporting the right of “self-determination”, at present noEuropean country desires German “reunification”. The fear of such a reunificationcan, however, become a highly destabilizing element for European policy, even withoutbeing able to prevent reunification. Whether reunification actually happens is, ofcourse, uncertain, but it cannot be excluded. In both German states there aredevelopments that make such a reunification more probable today than it was just twoto three years ago. A reunified Germany could and should not be neutral orneutralized. If at least the western part of the reunified Germany remains integratedin NATO, and the entire Germany is a member of the EC, then no threat would arisethrough a newly formed military and economically dominant superstate, which is thegeneral fear.

- 1

- Memo (translated from German):Austrian State Archive ÖStA, AdR, BMAA, II-Pol 1989, GZ.22.17.01/4-II.6/89. Written and signed by Thomas Nowotny,dodis.ch/P57516; also published in Wilson Center, doc. 165711. This memo wassent to all section leaders, the Cabinet of the Foreign Minister, alldepartments of the Political Section as well as to all Austrian diplomaticmissions in states participating in the CSCE. On 20 September 1989, ErnstSucharipa attached a note to this file entitled German reunification? Onthe ghost train ride of Department II.6. The statement should havebeen forwarded to the Section Heads, the Cabinet of the Federal Minister, alldepartments of the Political Section, the General Secretary, the AustrianEmbassies in Bonn, Berlin (East) and Moscow, the Austrian delegation in Berlinas well as to all Austrian diplomatic representations in states participatingin the CSCE. However, for unknown reasons, it was not forwarded. The note read:1) It is correct that there is again increasing talk everywhere aboutthe question of German reunification (or “new unification”, according toIISS Director Heisbourg). Basic consideration of the issues raised in theessay of department II.6 therefore seem inevitable in Austria. Here are thefirst brief remarks from the perspective of the Eastern Europe Department;2) In foreign policy, perception is often more important than reality:Despite the circumstances mentioned by Department II.6., which “trivialize”the dimension of a Germany consisting of the FRG and GDR, the impression(the fear) will persist in Eastern (and also Western) Europe that such astructure cannot be integrated into the European Peace Order. 3) Despite thepublicity-effective emigration movements from the GDR (Scale in 1989:approx. 100,000 citizens, of which approx. 5/6 “legally”, 1/6 “illegally”)there is a “GDR national consciousness” and pride in the benefits of its“own”, “other” German state, which is not to be underestimated. The silentmajority is still a majority even in the GDR. The slowly forming oppositiongroups want to keep their GDR (reformed and completely overhauled, butdistinct from the FRG). 4) In spite of Perestroika and Glasnost, the SovietUnion looks everywhere to strictly maintain the territorial status quo.German-political changes that go beyond, ‘change through rapprochement’ aretherefore not to be achieved without argument with Moscow.↩

- 2

- Franz Wunderbaldinger (*1927), dodis.ch/P52001, Austrian Ambassador inWest Berlin 1985–1990.↩

- 3

- Friedrich Bauer (*1930),dodis.ch/P51060, AustrianAmbassador in Bonn 1986–1990.↩

- 4

- During the ambassadors’ conference at the AustrianForeign Ministry on 8 September 1989 Wunderbaldinger noted: German-Germanrelationship: contractual regulations in many areas, strong contacts at variouslow levels. Large flow of visitors in both directions. Bauer later added: TheWest was not prepared for the so strongly desired reform process in the East,and has no concept. The FRG sees the EC as a place to embed itself in WesternEurope (leading it out of the status of a defeated country). Bonn wants toinclude the EC in its own policy on Germany. Relationship FRG-GDR: littleinformation about intra-German trade. Meeting of Bonn-Berlin representativesabout adapting intra-German to internal market rules. FRG seeks osmoticrelationship with GDR. Reunification in the Bismarkian sense is notsought. The head of the political section of the Austrian foreignministry ambassador Erich Maximilian Schmid summarized: The transformationprocess in the East was desired by the West, yet it was completely unpreparedfor this. The reduction of tensions resulted from the economic impossibility ofa permanent arms race. This should have been predictable. Processes in the Eastare to be assessed positively, but there is a danger of it spiraling out ofcontrol and resulting in destabilization. Austria welcomes upheavals in theEast, but these pose a danger that Austria could be associated with a kind ofgray zone in Central Europe. German reunification: a theoretical discussiontopic indeed, but not currently a reality. Cf. the minutes of theAmbassadors’ Conference, 1989; Working group East-West, Envoy JohannPlattner, Vienna, 8 September 1989, ÖStA, AdR, BMAA, II-Pol 1989, GZ.502.00.00/13-II.1/89.↩

- 5

- Willy Brandt (1913–1992), dodis.ch/P15409, Foreign Minister of the FRG 1966–1969 and Chancellor ofthe FRG 1969–1974.↩

- 6

- Nikita Khrushchev(1894–1971), dodis.ch/P14485, FirstSecretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union 1953–1964 and Chairman of theCouncil of Ministers of the Soviet Union 1958–1964.↩

- 7

- Bruno Kreisky (1911–1990),dodis.ch/P2507, Austrian ForeignMinister 1959–1966 and Federal Chancellor 1970–1983.↩

- 8

- IrvingKristol (1920–2009), dodis.ch/P57517,American author and social scientist, protagonist of the neoconservativemovement.↩